Risk benefit analysis (RBA)

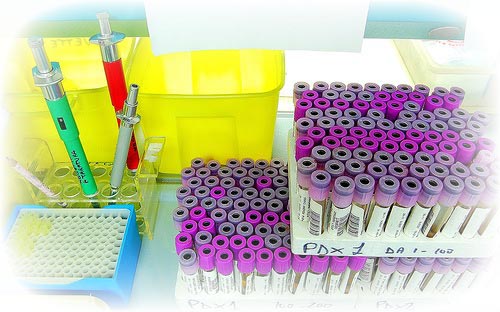

Risk benefit analysis (RBA) is a specific form of CBA which differs somewhat in its structure and outcome. RBA involves calculating and comparing the risk associated with a particular project, and comparing this to the potential benefits received from the project. RBA applies estimates for the level of risk associated with potential outcomes, both positive and negative. These risk estimates are then included in calculations of costs and benefits. In this sense RBA can be considered as a rational decision-making tool, as it not only considers costs and benefits, but also the risk associated with the occurrence of such costs and benefits. This form of project appraisal is widely used in health and medical analyses, of new vaccines or treatments for example, as well as in business to calculate the risk associated with certain activities to inform insurance premiums or other risk based decisions.

RBA specifically considers the costs and benefits associated with a ‘do nothing’ approach. The benefits of the ‘do nothing’ approach are costs which are not incurred if no project is undertaken. Meanwhile, the costs are the negative impacts associated with the ‘do nothing’ approach. Comparison of the ‘do nothing’ approach with a single or multiple project alternatives therefore provides the researcher with a more rounded understanding of the relative viability of a particular project.

RBA can consider a range of different forms of risk, including statistical risk and perceived risk. Statistical risk refers to the risk calculated from studies of previous projects using available data, for example, the probability of death among individuals using air travel. Perceived risk is the risk individuals intuitively associate with an activity or outcome. For example, personal risks are those risks associated with everyday life, which are faced in order to achieve certain benefits. However, when faced with additional risk, the majority of individuals are risk averse, that is they will try and avoid risk as much as possible. For this reason individuals sometimes make irrational decisions in relation to statistical risk, as they base their decisions on perceived risk. The relative difference between actual statistical risk and perceived risk therefore becomes important. This difference between the statistical risk associated with an outcome and the risk individuals perceive to be associated with an activity may be significant.

For example, consider Concorde air travel. Following the tragic accident on 25th July 2000 (see more here) a number of modifications were made to the aircraft before its re-launch in 2003. The statistical risk associated with flying by Concorde would have changed given the accident. However, the perceived risk associated with flying by Concorde, following media coverage and crash scene investigators enquiries, would have risen significantly. As a result, fewer passengers decided to continue flying with Concorde. Alongside the negative impact on air travel following 9/11, and with increasing costs, Concorde was subsequently taken out of service. Another simple example of this would be to consider the relative perceived risk levels associated with travelling by car and airplane. While most individuals are aware of the statistical risk associated with each, many still perceive incorrectly that air travel is the more risky of the two forms of travel.

Further varieties of risk include projected risk and real future risk. Projected risk is the risk level associated with an activity or project outcome calculated using models based on historical studies. For example, insurance companies may model the risk associated with different age groups of drivers to generate a project risk level associated with a young driver, to inform the premium they offer the young driver. Real future risk is the actual risk associated with an activity or outcome which is revealed when that activity has taken place or outcome has been realised.

Comparisons of the different risk types may be useful for the researcher in seeking to provide a robust analysis of risk. Comparing the difference between the projected risk obtained by modelling using historical data, with the real future risk or statistical risk associated with an activity or project outcome may highlight any failings of the current model. This would help the researcher to improve the model used in calculating projected risk for future projects/activities.

Summary of risk types

- Statistical Risk: determined through analysis of previous studies and available data.

- Perceived Risk: the risk level as considered intuitively by individuals.

- Projected Risk: risk calculated using models based on historical studies.

- Real Future Risk: actual risk revealed when a project is implemented, or activity is performed.

Criticisms of RBA

A key criticism associated with RBA lies in the calculation of risk levels. These probabilities or fractions cannot simply be arbitrary and require analyses of available data or historical studies. However, any such analyses suffer from some of the same key limitations related to data gathering which impact other forms of CBA. Missing data, or a lack of data on the risk associated with certain projects or activities, is a major concern. If a project is the first of its kind it would not be easy to calculate an accurate risk level associated with certain outcomes in the same way an insurance company can use the vast amount of data available on drivers to generate an appropriate risk indicator and therefore premium for a driver. Data availability is therefore a particular concern when calculating risk, just as it is when calculating values for costs and benefits in more standard forms of CBA.

Another problem faced by researchers is in accurately calculating perceived risk. While statistical risk and projected risk can be obtained by analysing data, albeit with a reliance on the quality of the data used in these calculations, for perceived risk it may prove more difficult to generate an accurate estimate of risk. This is because perceived risk changes over time, but also because methods of collecting data on perceived risk suffer from the same limitations associated with gathering data on individuals using revealed and stated preferences (read more on revealed and stated preferences).

- Discounting

- Discount/Compound

- Horizon Values

- Sensitivity Analysis

- Results

- NPV

- BCR

- Comparing NPV and BCR

- Downloads

- CBA Builder

- Worksheets/Exercises

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This resource was created by Dr Dan Wheatley. The project was funded by the Economics Network and the Centre for Education in the Built Environment (CEBE) as part of the Teaching and Learning Development Projects 2010/11.

Share |